8 months after the start of Ukraine’s invasion by Russia, Ukrainians are resisting, and fighting back. Heavy western sanctions have been imposed on Russia and, as a result, Russian oil and gas supplies to Europe have fallen sharply.

Energy “sobriety” has become the rule. Out of necessity because of extremely high prices for the unprotected sectors of the economy such as industry, which is experiencing unprecedented demand destruction. For the “protected” sectors, such as domestic consumers, governments are trying to limit consumption through voluntary changes in behavior, while providing shields against high prices.

Overall, the European Union has adopted a 15% voluntary reduction target for its gas demand between 1 August 2022 and 31 March 2023, compared to the average consumption in the past five years. In the end, load shedding could be enforced should it become necessary.

On the supply side, Europe has been very successful in filling up gas storages ahead of the winter, to a record 90%+ level despite the EU target for this year being 80%. This was achieved through a massive inflow of LNG cargoes, at the expense of Asia.

However, is the situation for next winter really secure? And at what price for the European economy?

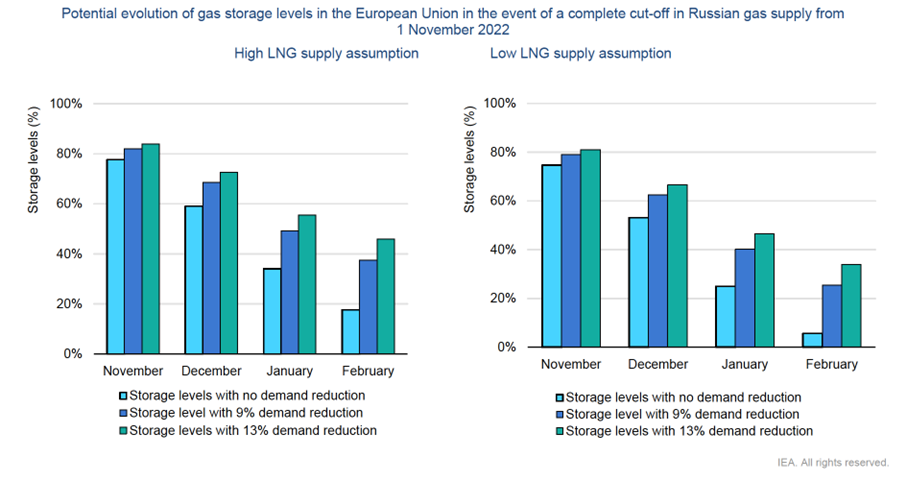

As highlighted by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its latest Gas Market Report, a late cold spell would be the Achilles heel of European gas supply security, in case of a complete shut-off in Russian gas supplies from November 1st:

Continued access to LNG supplies during the winter and “sobriety” in gas usage will be crucial to be prepared to face a potential cold spell hitting Europe in March – an unwanted late gift sent from Russia…

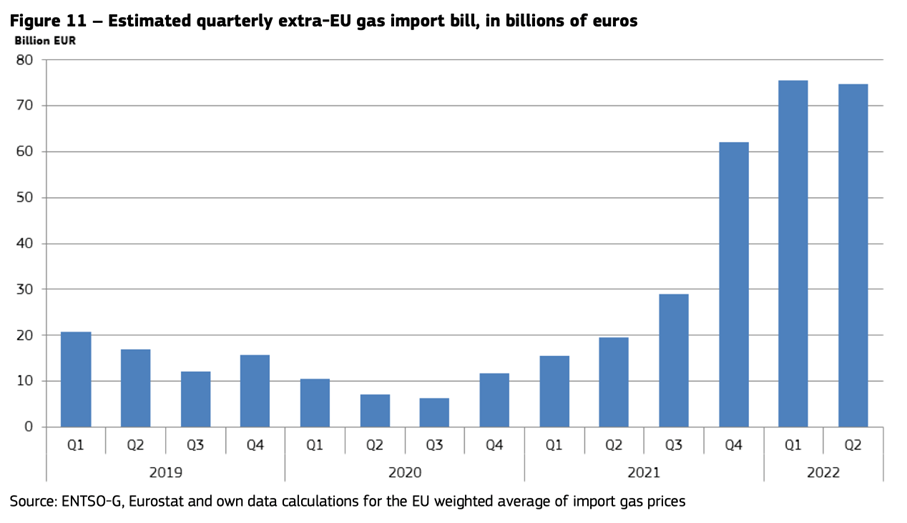

But this crisis has already come with an extraordinary high price to the European economy. As average import gas prices increased nearly four-fold since Q2 2021, the estimated EU gas import bill amounted to over €75 billion for each of Q1 & Q2 2022, compared to €20 billion in Q2 2021:

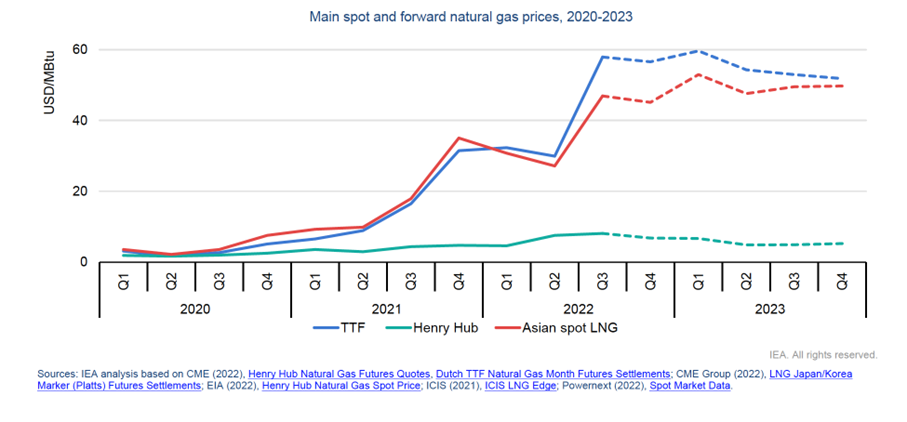

By and large, the missing pipeline gas volumes from Russia have been replaced by new LNG, mostly from the United States. These new volumes are now gas-indexed, mostly to the TTF benchmark, which is expected to retain its premium over Asian spot LNG prices during the 2022/23 heating season, thus further eroding European companies’ competitiveness, especially when compared to their US counterparts:

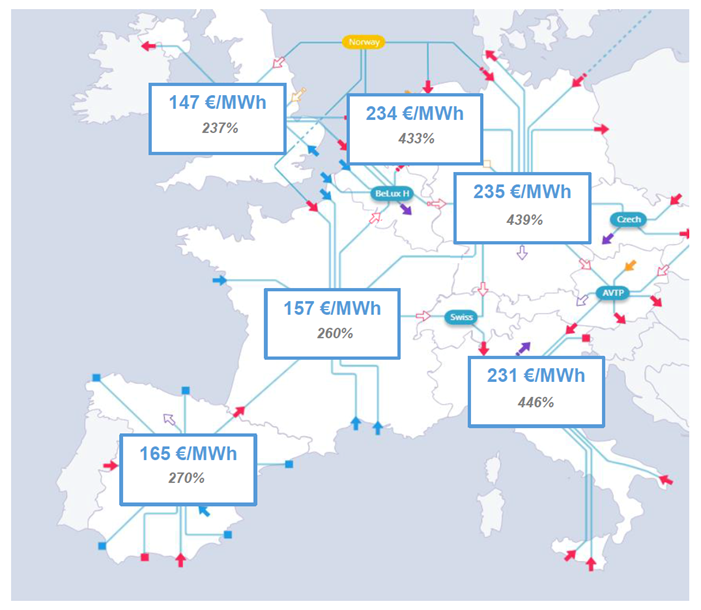

Most of the new LNG is delivered to Western Europe (Spain, France, UK), which has led to a strong divide in European spot prices in recent months:

Average European gas prices during August 2022 (and variations vs. August 2021)

Source: GRTgaz

Source: GRTgaz

A TTF-PEG spread of around €30/MWh since the start of the war in Ukraine reached over €120/MWh at the beginning of September, following the announcement of the total shutdown of Nord Stream 1.

This situation is not sustainable in the long-run, but will the EU Council decisions of October 20-21st have a lasting effect? France and Germany face deeply diverging situations, and lead 2 strongly divided “camps”:

- France has access to relatively abundant alternative sources of gas (in the form of LNG), to make up for lost Russian volumes, but is experiencing a tight situation regarding its power supply – with prices mostly driven by the high-priced TTF: a cap on the price of gas serving as a reference to the formation of electricity prices would be a welcome relief!

- Germany, on the other hand, is desperately short of gas, and sees any attempt at capping gas prices as a threat that would ultimately jeopardize its access to non-Russian gas. At the same time, it is relatively long in power (coal, lignite or nuclear), and sees the proposed uncoupling of gas and power markets (the “Iberian exception”) as a potential “leak” of subsidized power to other countries, including non-EU countries such as the UK, Norway, or Switzerland, while also encouraging a higher consumption of gas…

If the announcement of an EU Council “agreement” in Brussels on October 20-21st (to be confirmed by specific proposals of the EU Commission) has coincided with an easing of gas prices in Europe, this may be mostly due to the current mild weather experienced in Europe, full gas storages, and an unprecedented number of LNG tankers waiting to be unloaded, off the coasts of Spain in particular.

Will this last through the whole winter? If a cold snap were to hit Europe during the second half of the winter, storages would risk being fully depleted, making the 2023/2024 gas season extremely problematic: not much Russian gas will be available during summer 2023 to replenish storages, contrary to this year’s situation. Fortunately, the worst is not always certain… What will be key is to find ways to maintain a European unity to avoid divisions face to Putin’s Russia.

Philippe Lamboley