Throughout history, we have experienced several energy crises. In this article, we will analyze these crises, not only to understand the challenges we faced at each stage but also to discover how they have influenced current solutions and trends. Through a historical perspective, we will connect the key events and comment on their economic and political impacts.

A solid understanding of the past will give us the perspective necessary to analyze the present…

Oil Crisis of the 1970’s: How do politics and war impact energy?

In the 1970s, the main source of primary energy in the world was oil, with almost 50% of all energy coming from oil. Oil production is and was controlled by OPEC, with around 55% of world production and 80% of proven reserves in its hands. OPEC, in turn, is mainly made up by the Arab countries, which at the time controlled most of the production and reserves.

In 1973, Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack on Israel, triggering the Yom Kippur War in which Israel received support from some Western countries. In retaliation, the Arab OPEC countries decided to drastically reduce oil supply to Western nations that supported Israel.

This caused a dramatic rise in oil prices from $29.64 in November to $68.49 in January, an increase of 131.07%, and led to significant fuel shortages. Europe, highly dependent on oil from the Middle East, faced a severe economic crisis.

Following this first price rise in 1979, the Iranian Revolution and political tensions in the Middle East triggered a severe energy crisis as Iran reduced its oil production from 6 million barrels per day to just 1.5 million barrels per day. This drastic drop in production, coupled with political instability, significantly altered the global supply of crude oil.

The reaction in the markets was immediate, causing oil prices to skyrocket, doubling in just one year and reaching $121.74 per barrel. It is worth noting that prior to this crisis, oil historically moved between $25 and $35 per barrel. The price of oil experienced an increase of 247.83% over the previous historical high of $35 per barrel.

The economic impact was global. The crisis caused inflation, economic recession and an increase in living costs, especially in the most oil-dependent countries.

- Economic growth in the EEC fell from 5%-6% per annum in the previous years to a mere 1.3% in 1974, with some countries such as the UK, France and Italy experiencing technical recession.

- On average, inflation in the EEC rose from 7% in 1972 to over 13% in 1974. In the United Kingdom, it exceeded 20% in 1975. In countries such as Italy and France, prices rose around 10-15% due to high dependence on oil imports.

- Emerging economies such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China, which were not so dependent on imported oil or were already betting on cheaper energy sources, managed to maintain their competitiveness in the global market, especially in sectors like automotive, manufacturing and electronics, to the detriment of countries such as the UK and Germany. This marked a shift in the balance of economic power and a shift in competitiveness towards these emerging countries.

This situation prompted European countries to adopt key strategies to reduce their dependence on oil and improve their energy security:

- France accelerated its nuclear energy program, enabling it to generate more than 70% of its electricity from this source, while encouraging energy saving policies in household and industry sectors.

- The United Kingdom intensified resource exploration in the North Sea, reducing its dependence on imports. At the same time, restrictions were imposed on energy consumption and energy efficiency was encouraged. After the 1979 crisis, oil and gas production increased.

- Germany diversified its energy mix with coal, natural gas, and nuclear energy. In 1979, it intensified its investment in nuclear energy, seeking greater energy independence.

- Spain adopted energy rationing measures, such as reduced working hours and blackouts, and accelerated its nuclear energy program, as well as measures to promote the use of domestic coal to counteract dependence on oil.

In the 1960s and 1970s, oil and coal dominated the global energy landscape. However, the oil crisis of the 1970s marked a turning point, forcing Europe to diversify its energy mix. Nuclear energy emerged as a key alternative, while renewable energies began to gain relevance.

Since the 1980s, Europe has moved towards a diversified energy mix. Nuclear energy was consolidated as a stable source, natural gas grew due to its lower environmental impact, and the use of coal decreased. In the 1990s, the European Union pushed for market liberalization and promoted renewables such as wind and solar, along with advances in energy efficiency. Today, it combines renewables, gas, nuclear and emerging technologies to ensure security, reduce emissions, and meet future challenges.

Current Energy Crisis

After the 1970s oil crisis, Europe was motivated to diversify its energy mix, consolidating nuclear power, reducing the use of coal and increasing the importance of natural gas and renewables such as solar and wind. Since the 1990s, market liberalisation and a focus on energy efficiency have accelerated this transition, and today Europe combines various sources, including emerging technologies, to ensure security, reduce emissions, and meet future challenges.

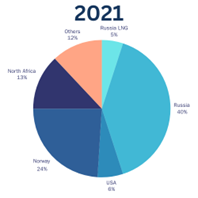

In 2020 Europe had a significant dependence on Russian gas imports, with 45% of European gas consumption coming from Russia as shown in the graph on the right. Nuclear energy, although it provides stability to the system and there are sufficient uranium reserves, faces challenges related to safety and negative perception, especially after the Fukushima accident. Renewable energies, such as solar and wind, have gained prominence, but their non-dispatchable nature creates challenges in terms of stability and energy security.

In 2020 Europe had a significant dependence on Russian gas imports, with 45% of European gas consumption coming from Russia as shown in the graph on the right. Nuclear energy, although it provides stability to the system and there are sufficient uranium reserves, faces challenges related to safety and negative perception, especially after the Fukushima accident. Renewable energies, such as solar and wind, have gained prominence, but their non-dispatchable nature creates challenges in terms of stability and energy security.

The COVID-19 pandemic marked the beginning of a global energy crisis by abruptly altering energy demand and supply. During the 2020 confinements, energy demand fell sharply, leading to reduced oil and gas production and disinvestment in new infrastructure. However, with economic recovery in 2021, demand grew disproportionately, especially in Europe and Asia, while supply failed to adjust, exacerbated by logistical problems and global competition for resources such as natural gas.

In addition to COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 intensified this energy crisis. Europe faced cuts in Russian gas supplies (45% of European consumption) due to Russia’s decision to use gas as a tool for political pressure following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, including the reduction of flow through key pipelines such as Nord Stream 1 and its subsequent sabotage. This was compounded by disruptions to routes through Ukraine and the EU’s decision to reduce its dependence on Russian gas as part of economic sanctions. These factors destabilised the energy market, causing gas and electricity prices to rise dramatically.

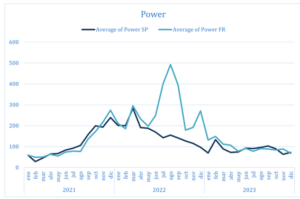

All this geopolitical tension was reflected in gas and electricity prices. The gas price reached an all-time high on the day-ahead market of approximately 312 EUR/MWh in August 2022, compared to a peak in 2019 of just 22.41 EUR/MWh. At the same time, electricity prices reached record levels: in Spain, the spot market peaked at 700 EUR/MWh in March, while in France prices reached 3,000 EUR/MWh in April, showing the severity and impact of the situation on European markets. Climatic factors limiting renewable production and dependence on fossil fuels left Europe particularly exposed.

During this energy crisis, the widespread increase in energy costs generated profound economic and social repercussions. Industries faced a significant increase in their operating expenses, affecting both their competitiveness and their production capacity. This, in turn, contributed to an acceleration of inflation, making basic goods and services more expensive, while consumer purchasing power declined sharply. These dynamics intensified pressure on households and aggravated economic inequalities.

In the graph below, CPI and GDP are compared with oil and gas prices in different countries. It clearly shows a decrease in both GDP and CPI from 2022 onwards, coinciding with a significant increase in the prices of these commodities.

The European Commission’s main measures to manage this energy crisis:

These events highlighted the vulnerabilities of the European energy system and underlined the urgent need for diversification and transition to more sustainable and resilient sources.

- Energy supply diversification:

- The EU worked intensively to reduce its dependence on Russian gas. In 2021 about 45% of its gas imports came from Russia, but by 2023 this was reduced to 15%.

- Additional imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from countries such as the United States and Norway accounted for 19% and 30% of total gas imports in 2023, respectively.

- Temporary reversion to fossil fuels: To ensure energy security, several European countries reactivated coal-fired plants, temporarily delaying emission reduction targets. This crisis forced many countries to postpone their 2030 targets and extend the deadlines for meeting them. Germany, for example, had to turn again to coal to meet energy demand, while France focused its efforts on increasing nuclear production.

- Gas Storage:

- The EU reached more than 90% storage capacity in 2022, exceeding the minimum target of 80%. This helped ensure security of supply in the face of winter.

- Demand reduction:

- Through the Gas Demand Reduction Plan, gas consumption decreased by 15% during August and September 2022 compared to the average of the previous five years. This was complemented with measures to incentivize renewable energy and energy efficiency.

- Joint purchase of energy:

- The “AggregateEU” platform facilitated the coordinated purchase of gas to avoid competition between member states. During 2023, several joint purchasing rounds were organized, securing 42 billion cubic meters of gas for the region.

- Investments in energy infrastructure:

- Key projects, such as the gas interconnections between Poland and Lithuania (May 2022) and Greece and Bulgaria (October 2022), strengthened the resilience of the network.

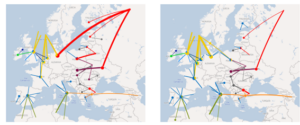

As the graph below shows, since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the reduction of Russian gas imports by the European Union, gas flows in Western Europe have changed direction: they now go from West to East. France, Spain and the Netherlands lead LNG imports, with the United States as the main supplier. Meanwhile, Norway remains the main source of pipeline gas, offsetting the decline in Russian flows with increased supplies from Norway, the United States and North Africa.

Overview of physical gas flow to Europe 2021 (left) vs. 2024 (right)

At the national level, each country adopted strategies adapted to its energy mix and economic situation, but all shared the objective of reducing their energy vulnerability and alleviating the pressure on consumers. More information can be found in previous articles, such as; Rising energy prices: national measures to protect European end-consumers and Margin Cap: the new paradigm.

We have seen how, throughout history, we have been dependent on countries controlling key energy resources. During the 1970s, oil dominated as the main energy commodity, and the Yom Kippur war and its aftermath forced us to look for alternatives to reduce dependence on oil. We have oscillated between gas and oil in a constant attempt to diversify. This pattern was exposed again with the energy crisis of 2022 when this dynamic manifested itself again with a heavy dependence on natural gas from Russia, forcing us again to diversify.

The EU’s energy transition is currently closely linked to its dependence on critical raw materials (CPMs) and advanced technologies. CPMs such as lithium, cobalt and nickel are essential for renewable energy infrastructure, electric vehicles and energy storage, but their supply is highly concentrated in a few countries (mainly China). Similarly, technologies such as semiconductors and AI are key to optimising energy systems, managing renewable energy generation and improving energy efficiency.

The question seems to be what the next energy crisis will be, and how we can prepare for it. History suggests that energy resilience will depend not only on diversifying sources, but also on strengthening technological self-sufficiency and key infrastructures.

Irene Sánchez-Haro Montero