Almost five years after the publication of RED II (Renewable Energy Directive), three years after the announcement of Europe’s ambitions in hydrogen, two years after the entry into force of RED II, more than two years after the inclusion of hydrogen in the French energy code, one year after the Commission authorised public aid of up to 5.2 billion for the H2Use IPCEI (Important Projects of Common European Interest) for the production of renewable hydrogen, and after years of preparation, discussions, consultations and a spectacular turn of events, the European Commission’s delegated acts defining the criteria for specifying renewable hydrogen and classifying its derivatives produced in Europe (or imported) were finally published on June 20th.

Europe finally has a definition for renewable hydrogen! Hallelujah !

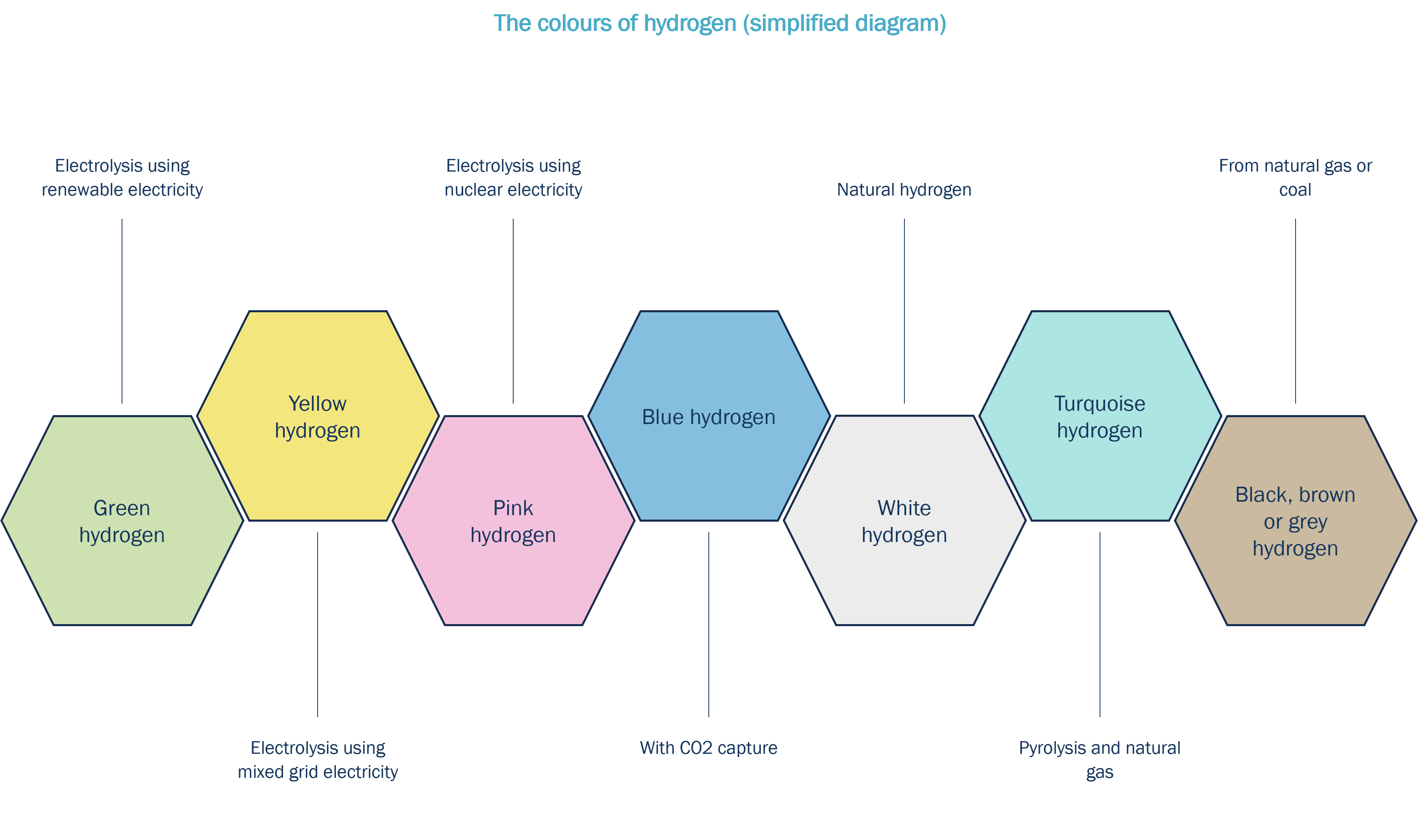

This newly certified hydrogen will therefore add a new hue to the already diverse H2 kaleidoscope: “Green Europe”. Positioning this colour on the colour chart can sometimes become a difficult exercise, often subjective and regularly susceptible to regional colour blindness. While each country will certainly see its hydrogen in a beautiful spring green, some (on the other side of the Rhine?) will think they see French hydrogen tending towards pink, while many other products will appear in much darker shades, or even a dubious yellow.

The text of these delegated acts does not lead naturally to serenity. These abundant and complex rules (21 pages) provide for several ways of supplying electrolysers with renewable electricity, depending on whether they are connected physically (direct line) or virtually (Power Purchase Agreements) to solar or wind farms, or are used to provide flexibility to the grid during periods of congestion.

These regulations, which apply to both domestic production and imports into the EU, are already having an impact outside Europe, with intense debates in the United States about the possibility of introducing similar rules – such as the ‘additionality’ and spatio-temporal correlation criteria – or in Japan, which has decided to adopt a similar threshold of 3.4 kgCO2eq/kgH2 (-70% GHG) to define the decarbonised nature of the hydrogen produced.

A great deal of work remains to be done to achieve an international harmonisation of standards.

Under particular scrutiny, these rules finally define renewable hydrogen within the meaning of this directive. And should, therefore, begin to provide the stability and legal certainty so eagerly awaited by investors and manufacturers, without which business models and investment decisions could not be completed. These delegated acts finally specify the conditions under which electricity drawn from the grid can truly be considered renewable. However, given the complexity of this text and the controversies that still surround it, the debate on electricity and greener-than-green hydrogen will not be over with the publication of this text. The enthusiasm shown by Mrs Kadri Simson’s (European Commissioner for Energy), who expressed her delight on Twitter when the texts were published, should be tempered: “This means legal certainty for producers and consumers of renewable hydrogen and is a crucial step in attracting investors…“.

In the general case, electricity must be purchased “directly or indirectly” from one or more additional renewable sources. For the Commission, this means: (i) unsubsidised, (ii) commissioned at the same time as the electrolysers (with a tolerance of 36 months), (iii) geographical correlation must be respected (~same bidding zone, country), and finally (iv) time correlation that should eventually be (2030) on an hourly basis.

We note that these criteria are particularly suitable for projects that are sometimes described as “neo-colonialism energy”, allowing “green” production to coexist with an electricity system that is rich in CO2 emissions (in this case, this “green” hydrogen would have to be subject to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, but that’s another story), but seem particularly unsuitable in European countries developing renewable energies mainly via feed-in contracts, often in the form of two-way CfDs[1]

In practice, these delegated acts contain two important pragmatic provisions:

- Any project commissioned before January 1st, 2027, will be able to use “non-additional” renewable electricity, i.e., electricity that may have been commissioned long before the startup of the electrolysers and that may have benefited from subsidies, until January 1st, 2038.

- Above all, these acts grant special status to reward electricity mixes that are already decarbonised, either through a very high penetration of renewables or a mix of renewables and nuclear. Projects located in countries (bidding zone) where the intensity of emissions attributable to the electricity produced is less than 18 gCO2eq/MJ (64.80kgCO2eq/MW) will be able to use “non-additional” renewable electricity.

Metropolitan France should be below this threshold, but we still need to agree on the emissions factor for the French mix. In the annex, the Commission proposes a high factor (19.6gCO2eq/MJ), making no distinction between mainland France and the French overseas territories. However, the rules allow for the use of alternative methods and data sources, which should enable the emission factor of the grid to be recognised at its true value by restricting its scope to mainland France (bidding zone).

Guarantees of origin

This delegated act remains relatively quiet on the use of guarantees of origin in its requirement to conclude “directly, or via intermediaries, one or more renewables power purchase agreements with economic operators producing renewable electricity in one or more installations generating renewable electricity for an amount that is at least equivalent to the amount of electricity that is claimed as fully renewable and the electricity claimed is effectively produced in this or these installations”.

This reference to guarantees of origin is only present under premise 15 of this delegated act: ” Article 19 [of RED2] should avoid that both the producer of the renewable electricity and the producer of the renewable liquid and gaseous transport fuels of non-biological origin produced from that electricity can receive guarantees of origin by ensuring that the guarantees of origin issued to the producer of renewable electricity are cancelled”.

Although it is not explicit, we therefore understand that the renewable nature of the electricity purchased “directly or indirectly” from one or more renewable sources and consumed by electrolysers will have to be proven by a corresponding guarantee of origin. Based on the characteristics of this guarantee, the additionality and spatio-temporal correlation requirements can be verified.

Therefore, for France (subject to emissions intensity being well below 18gCO2eq/MJ) we understand that the conditions of this delegated act will be fulfilled if the “intermediary” (supplier) cancels an amount of guarantees of origin from France each month for a quantity equivalent at least to the amount of electricity declared as entirely renewable.

From 2030, the time correlation should be hourly, which should lead to a change in the organisation of the system of guarantees of origin in France (they are currently issued on a monthly basis).

Conclusion

This delegated act continues to be the subject of much (justified) criticism, particularly from the European Parliament, and it is highly likely that this standardisation work will be amended before the end of the transitional phase (in 2027). There is even talk of one of the articles of RED III (currently being finalised) cancelling and replacing this delegated act.

Does Europe have a definition for renewable hydrogen?

[1] Contract for Difference

Philippe Boulanger