The fight against climate change has become the focus of the energy sector’s development. The objective of zero emissions by 2050 is central to the world’s energy strategy. However, not all countries are beginning this process from the same starting point. In the coming decades, most of the world’s emissions will originate in countries with current emerging economies, that is, they undergo an industrialization / urbanisation / electrification process as they grow. In its report dated June 2021, the IEA focuses its analysis on the need to encourage investment in clean energies in these countries and recommends a number of incentivization mechanisms.

We, at the HES, would like to make our readers aware of this relevant IEA report and share with you its main conclusions.

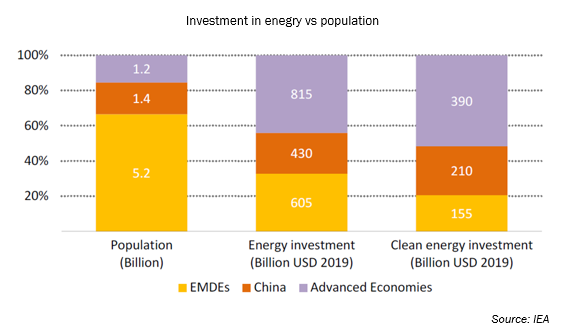

Energy transition requires a huge amount of investment. In the case of developing countries (emerging economies), the needs are proportionally larger, and the economic effort is far beyond their means. These emerging economies are home to two thirds of the world’s population, while only one third of global energy investment is allocated to them. This figure drops to 20% when it comes to investment in clean energies.

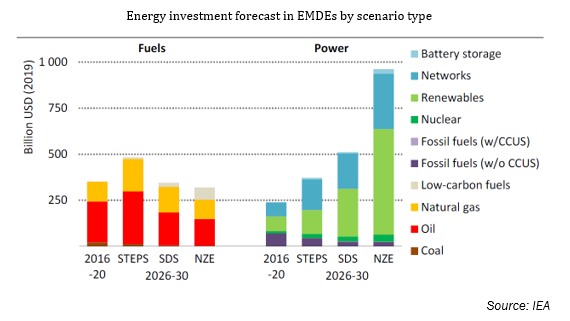

In its report, the IEA analyses three different scenarios depending on the development of the energy targets:

- Zero Net Emissions Scenario (ZNE): where all countries reach the zero CO2 emissions target by 2050, with developed economies reaching it before this date.

- Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS): this scenario foresees universal access to energy in 2030, zero emissions target in 2050 for developed countries, 2060 for China and 2070 for EMDEs (Emerging Markets and Developed Economies).

- STEPS (Stated Policies Scenario): this scenario is a baseline scenario and does not reach the 2050 target. It points to the baseline situation, the initial framework, and current conditions and policies, including the impact of Covid-19. This scenario provides an assessment of the direction current global energy systems are heading to and allows for a comparison with the ZNE and the SDS.

Based on these scenarios, the IEA provides an overview of the investment needed in emerging economy countries so as to reach these scenarios between 2026 and 2030.

According to the scenarios put forward by the IEA, investment in EMDEs must increase significantly to meet climate targets. Investment in clean energy generation will be paramount. However, larger investments in electricity infrastructure will also be needed as its current state will not allow for the electrification of clean generation technologies. Energy efficiency will be, as in the rest of the world, an essential vector for the desired change. By way of example, the SDS scenario will require approximately a three-fold investment in renewable energies and electricity grids. Meanwhile, decreasing investment in oil, slightly increasing investment in natural gas (which has a large room for improvement in terms of efficiency and environmental impact) and investing in low-carbon fuels will also be required.

Furthermore, and depending on the area of investment, the IEA points to a number of key factors for these investment programmes to become successful:

- Investments in renewables will concentrate most resources. The effectiveness of the investments will depend on the choice of source (solar or wind) according to local resources, the level of development of the country’s supply chains, cost of land and level of transmission infrastructure, etc.

The development of renewable generation will be particularly difficult in countries where the economy is based on the export of fossil fuels. Given their privileged access to this energy source, most of these countries do not have any policies to promote renewables. The IEA highlights the role that extraction companies (many of them owners of renewable resources) must play in the transformation of these countries.

- Electricity grids are the backbone of the future of energy. Investing in them will also be very important. New grids must not only adjust to the growth in demand (with increasing electrification of the population) but also be prepared for the integration of renewables.

Most of these countries currently have obsolete infrastructures, managed as state-owned utilities, financed by governments, and operated as vertically integrated monopolies.

In order to attract private investment towards these initiatives, new regulation will be necessary. The IEA recommends models such as BOOT (Build, Own, Operate and Transfer). Under this development model, a private company is granted a concession for a period of time, allowing it to both invest in and finance the grid extension. The company will operate it for 20-25 years and then transfer it back to the granting authority.

In this area, the promotion of “Smart grids” is also recommended, as it can enable the electrification of unconnected areas. In this context, it is recommended that a regulatory framework be created to order decentralised development, allowing for the future integration of these type of grids.

- Energy efficiency and fossil fuel substitution. In rapid energy transitions – as is the case here – improvements in the use of fossil fuels should not be underestimated. Investment in this area should focus on improving the efficiency of their technologies and reducing emissions.

One recommended option for the gradual substitution of fossil fuels is low-carbon fuels. Investing in these fuels should first consider local conditions to assess the feasibility of projects. Technologies based on biogas production, hydrogen or biodiesel production using hydrogen-treated vegetable oil (HVO), etc. are recommended.

It is clear that energy transformation is a key factor in the fight against climate change. Energy change in emerging countries is essential to achieve global targets. Investment needs in these countries are enormous and disproportionate to their resources. This leads us to the need of creating real solidarity between rich and developing countries. Finally, the efficient way to undertake these investments will be via private initiative (subsidised by way of development policies).

It remains to be clarified how to attract the necessary capital to these countries to carry out this massive energy transformation. Even more so when considering the limited legal certainty in some of them and that, in any case, most of them do not have regulatory policies and legal frameworks to encourage this investment.

In short, the task is clearly defined. All that remains is its implementation. The future of our world depends to a large extent on our ability to implement these policies.

Guillermo Llanos