On 9 January, a Catholic church in Immerath, a city in western Germany, was destroyed to make way for the expansion of a gigantic coal (lignite) mine operated by RWE. This demolition took place in spite of protests by residents and environmental campaigners.

These images, which seem to come from another time, evoke the drama of the village of Tignes being swallowed up in 1952, the last inhabitants having to be evacuated by force by the police. But at the time, Tignes had to support efforts to rebuild the country, and the electricity involved was green (even if electricity then was colour-blind).

We’re also learning that, in Germany, the displacement of people in connection to coal mining is also affecting Lusatia, an eastern region near Poland, where entire villages have been wiped off the map. In 2007, a 750-year-old church was moved 12 kilometres from Heuersdorf to Borna (in the East) on two rolling platforms, at a cost of 3 million euros, in order to prevent its destruction.

Indeed, Immerath had already become a ghost town in 2013, when its 900 inhabitants, their houses, the 18th-century Stations of the Cross and other village monuments were relocated to Immerath Neu, a new site sprung from the earth in the same municipality of Erkelenz, in North Rhine-Westphalia, as part of an immense relocation plan affecting a total of 7,600 inhabitants of the region.

The environmental campaigners, with banners covered in slogans such as, ’He who destroys culture also destroys people’, were powerless to stop it.

This ‘minor news item’ reminds us that, beyond political discourse, the reality of electrical power generation in Europe in general and Germany in particular continues to be dependent on coal: coal and lignite still produce 40% of Germany’s electricity.

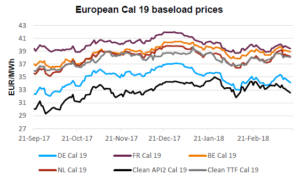

The price of coal is therefore still the primary factor in the indexation and evolution of electricity prices on the continental plate. (see figure below):

While Germany has just created a new grand coalition government (CDU/CSU/SPD) with the signing of a new government contract (Koalitionsvertrag) introduced on 7/2/2018, we can legitimately ask ourselves: what will remain of October 2010’s Energiewende?

This energy revolution had been written into the Koalitionsvertrag of a similar grand coalition at the time, and called in particular for a 40% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2020 (with respect to the 1990 level), an 80% reduction by 2050 and a higher penetration of renewable energies in the electrical power generation market: 35% in 2020, 50% in 2030, 65% in 2040 and 80% in 2050.

Germany is ahead of the game in this latter goal, with 38% renewable energy, and the new government has even committed to reaching 65% from 2030 (i.e. 10 years early). On the other hand, the coalition agreement remains silent on the objective of reducing CO2 and specifies that the exit from coal must be made step-by-step (schrittweise).

In this respect, with a reduction of only 27.9% in 2015 (and a slight increase since then), the target seems permanently out of reach. Agora Energiewende even predicts that the 2020 target will be missed by…120 million tons of CO2 equivalent (i.e. more than 4 times the total emissions of the French electrical power sector in 2016).

It truly seems that, faced with the choice of a policy of industrial development (roll out of renewable energies) or of combating climate change, the decision-makers are clearly demonstrating their agnostic pragmatism.

And churches can fall…

Philippe Boulanger