Year 2020 would have been a very special year for the Capacity Mechanism Market, too. It would have started “normally” following the 2019 trend. However, the pandemic and its procession of consequences and restrictive measures then reshuffled the cards on the Capacity Market and drove up the prices of Capacity Guarantees when, on April 6th, 2020, EdF decreased its electricity production forecasts in France for the year 2020 because of the health crisis. Such prospects were to force RTE (the French TSO) to set off the alarm by announcing, on June 11th, 2020, the likelihood of a system tension during the 2020-2021 winter period caused by the forecasted capacity unavailability of part of the nuclear fleet. A look back at an eventful year that was to expose the behind-the-scenes mechanics of the Capacity Mechanism in France.

Following its June announcement to stimulate the system and ensure that the shortfall of capacity was to be covered, the TSO adopted a number of exceptional measures, the main ones being:

- The removal of charges for upward capacity adjustment applying to the 2020 and 2021 delivery years (DY 2020 and DY 2021);

- The removal of fees for late certification of new demand response sites for 2020 and 2021, and

- The organisation of additional auction sessions for the 2020 delivery year.

These measures did not have a significant impact on the balance of the system, as the additional capacities contracted remained insignificant.

Nevertheless, on November 19th, 2020, RTE changed its position in its note about getting through the winter 2020-2021 winter, deferring the major risk of tension to the second part of the winter period, even stating that the “situation was more favourable than initially expected in the spring”. A statement apparently insufficient to curb the fire started during the summer with regards to the AL2020 capacity mechanism.

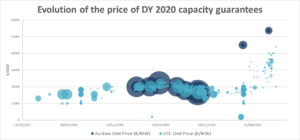

It is within this context that, after closing the year 2019 with an auction price of 16.5 k€/MW – which set the Reference Price for Imbalances, the “PREC” for the year 2020 – the price of the Capacity Certificate peaked in June and September of this year, exceeding the 50 k€/MW mark to close the year at 40 k€/MW for DY 2020, 39 k€/MW for DY 2021 and 18.2 €/MW for the year 2022. A boom in which the choices and communications of the TSO played a leading role.

What lessons can we learn from this year 2020?

1) A conservative position of RTE and a lack of perception on the part of certain players

As far as RTE is concerned, the system balance forecast put in place, with the exception of the November update, have not enlightened the players sufficiently. The supply-demand balance for 2020 should, in fact, be less tense than what RTE showed in its announcements. In its analyses, the TSO used the forecast certification level updated by the producers, but combined it with a very conservative approach on the obligation (demand) side – which should also have been considerably affected downwards by the Covid crisis19.

On the players’ side, at the time of the December 2020 auction, a relaxation of the stress on the price should have been observed on the supply side but especially on the demand side. And for a good reason: on November 19th, RTE had presented an update of its vision of the supply-demand balance on the Capacity Market. This new information showed an improvement in the market balance for the 2020 delivery year, which resulted, in particular, from an upward revision of nuclear availability and a downward revision of capacity obligation forecasts.

The conclusion reached is that the Capacity Mechanism did not give clear signals at all times and/or that actors were unable to react to the very numerous and sometimes contradictory information provided by the TSO.

Furthermore, the result of the June auction for the 2022 delivery year raises some questions, as the system did not appear to be under tension for the year 2022.

2) In the end, a mechanism that is closer to an automaton than to a market

Nuclear capacity is the technology that sets the auction price and can keep the capacity certificate at low price levels in case of a potential tension of the system. Last June and October, with delays in nuclear maintenance having forced the nuclear industry (to secure capacity for winter 2020-2021) to review its shutdown schedule from top to bottom, nuclear capacities did not participate in the auctions for the 2020 delivery year… And prices soared, the absence of the puppeteer throwing a harsh light on the mechanisms of an automaton usually operated by the price “plateau” set by EDF for its nuclear capacity and mostly followed by the obliged actors.

In addition, even if the supply-demand balance were to appear to be in great surplus, over-the-counter exchanges and auctions would not be able to bring prices down on a lasting basis, mostly due to the bilateral oligopoly structure and the imperfect information situation in which the actors of the mechanism find themselves.

3) In case of apparent tension, the OTC market disconnects from the auctions.

The DY 2020 OTC market prices remained lower than those of the auctions. While the OTC price gave a signal 20% to 30% lower than the auction price, it still remained higher than the PREC (Reference Price for Imbalances). Which of the two capacity auctions or OTC deals gives the price signal that best reflects the equilibrium of the mechanism?

4) The consumer is the one who finances the imbalance in the capacity mechanism whatever its origin. For what purpose exactly?

Let’s start with a simple description of the fundamentals of a market and a mechanism.

A market relies almost exclusively on one essential factor: the price indicator that enables production to be adapted to demand.

This precision shows essential in view of the common use of the term Capacity Market, which sometimes makes us forget that the Capacity Mechanism is, indeed, a mechanism applied to a market. A mechanism that aims, above all, to secure the community’s electricity supply in times of system tension (by ensuring a balance between supply and demand) while maximising the utility function of this system security.

But should this mean that consumers must bear the consequences of a potential imbalance at all costs? Even if the cause is a lack of capacity, far beyond from the consumer’s responsibility? This question deserves to be asked.

For the 2021 delivery year, consumers will see their electricity bills increase quite significantly compared to 2020, in particular because of this capacity component. These increases should be visible during the revision of the regulated sales tariff and on market prices, whether they are indexed to the Regulated Tariffs or not. This would mean telling consumers: “next year, using electricity at peak times will cost you more because there is not enough capacity and we need to encourage new capacity to come into the system to secure of your electricity supply”.

So, what is the actual problem? The problem is that this price signal is not relevant on the supply side. This sudden price increase does not, as we have seen in 2020, allow for the mobilisation of significant short-term capacities that would ease the system’s tension.

As an illustration, if in the DY-1 year-end auctions (in particular, the December DY-1 auction), the market is seen as tense, the prices of these auctions should normally be high and, most importantly, should constitute a signal for the deployment of new capacity. However, from December DY-1 to the first PP2 days of January DY, it is simply impossible to deploy any new capacities.

On the demand side, this price signal is more adequate since it pushes the obligated Parties to reduce their consumption during peak hours (PP1). Still, this signal will only be readable by those connected to a voltage higher than 36kV. Due to a strange rule of the mechanism, the rest of the actors, especially the residential ones, will not be able to avoid the extra cost by reducing their consumption.

In short, and regardless of any “acceptable price” paid by the consumer to send a signal to the market, the latter would remain in deficit in the short term.

Consequently, wouldn’t a short-term price increase not supported by fundamentals result in making the community pay a premium rewarding already available capacities (when these would have been present anyway)? The administered price ceiling (60 k€/MW currently) would hence only be there to set a maximum size for the hole in the consumer’s wallet…

What is the near future for capacity prices?

This year, we were able to witness all possible situations on the price of capacity: a surplus market for the 2019 delivery year with a price close to 0 €/MW; a tight market for DY 2020 and DY 2021 with a price close to the maximum set by the rules, namely 60 k€/MW; and a tight market for DY 2022 (in June 2020 auction).

For the 2021 delivery year, RTE had warned last November of an increased risk of tension due to doubts about nuclear availability during the first quarter of the year. Obligated players will therefore have to be very vigilant and implement the appropriate strategies to complete their purchases/sales according to the evolution of the supply-demand balance.

For the 2022 delivery year, with the return to ‘normality’ of nuclear power and plans to develop renewable assets, prices should logically fall, but all this remains at the discretion of the dominant player: The implementation of purchases/sales strategies over the medium term should be considered.

If these reversals undoubtedly made some people happy and also caused some grinding of teeth, they will, most importantly, have made a multitude of players aware of the TSO’s preponderant influence on the results of the auctions and of the importance of implementing robust strategies in this cyclothymic mechanism!

Ibrahima Baldé