The capacity mechanism is a cornerstone of the French national energy independence. With the deployment of renewable generation and the decision to phase out coal and fuel-oil generation, matched with ageing nuclear powerplants, the need made itself felt in the early 2010’s to ensure enough capacity was available during peak hours to avoid system failures. In particular, there were some capacities which were not profitable overall because they could produce at a margin only a few hours a year. Therefore, the rationale of the mechanism was to help keep these capacities in the market and encourage the development of new ones. After a request made to the European Commission, which was contrary to interference in the energy market, to accept the new mechanism, France opted for a decentralized capacity mechanism, in theory more coherent with free market principles, whose objective was and is to guarantee the long-term security of electricity supply in France. Entering into force in January 2017, the current mechanism is set to expire in 2026, after a decade of operation. Important high-level discussions are underway for the development of a new mechanism, which could continue being a major source of revenue for many actors for decades to come.

The current French capacity mechanism is based on a singular arrangement, universal and decentralised. Universal because any contributor to system reliability, producer, or demand side provider, receives the same payment with no discrimination by type or technology depending on its actual contribution to system reliability. Decentralised because the exchange of capacity occurs between contributors and demanders (customers). Each electricity producer (or demand side flexibility provider) must certify their production capacity at the height of their expected availability during peak hours.

EdF image showing how during peak hours, even with all technologies employed (right) there might not always be enough power available

Meanwhile, each supplier is required to obtain capacity guarantees to cover the consumption of all its customers during periods of peak national consumption. Producers can sell their guarantees to suppliers or traders, bilaterally or through organized auctions. The contribution and obligation of actors are measured on days designated as peak days by the TSO, during peak hours: from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. and from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m., i.e. 10 hours. Peak days are of two types, PP1 and PP2. PP1 days apply for consumers, while PP2 days apply for producers. There are a maximum of 15 days PP1 and 25 days PP2 per year.

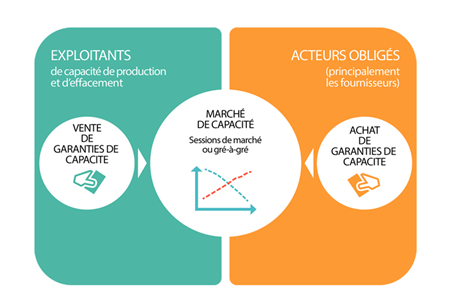

RTE image showing producers (green) and suppliers (orange) exchanging capacity contracts for a given year.

Although the capacity mechanism was successful in bringing a significant new source of revenue to actors (especially electricity producers), and consequently ensuring the French system stability during peak days, several actors now perceive that the system has several drawbacks: complexity; price volatility; main actor’s role; and lack of foreseeability.

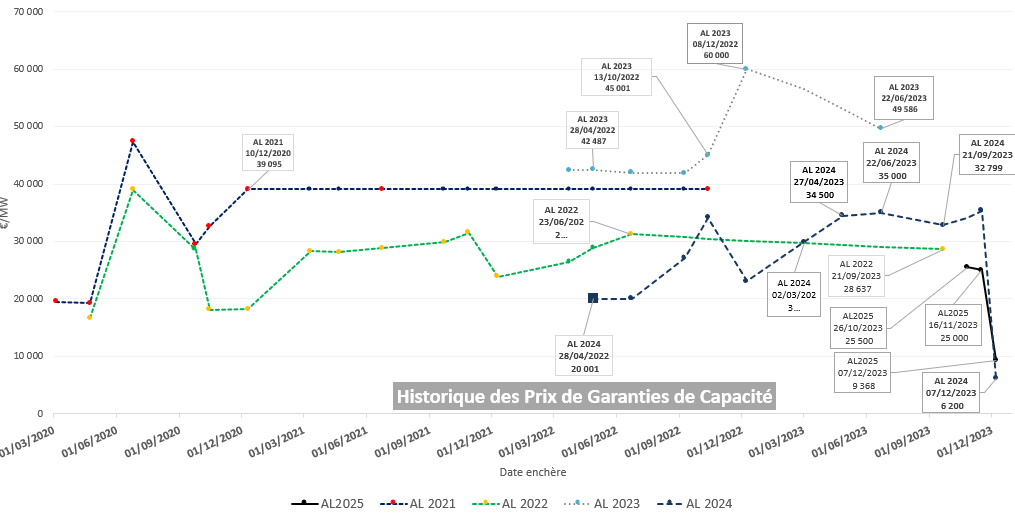

Even several years onwards, most of major market players have a limited understanding of the intricacies of the system and tend to have a sub-optimal participation to the capacity certificate’s market. Moreover, some large market players, in particular national energy company EdF, have a preponderant effect both on the supply and demand side during auctions. Coupled with the fact that actors, unlike what was idealised, do not certify 4 years in advance but often do so at the last minute, this overall situation leads to huge changes in supply and demand from one auction to another. In turn this entails two issues: a difficulty in foreseeing the true availability of production and flexibility capacities for a given year, leading to increased system risk, and a significant price volatility introducing a financial risk for producers, suppliers and consumers. For example, the last auction of 2022 for contract 2023 settled at a price of 60k€/MW, meanwhile the same auction a year later, for the contract 2024, settled at 6.2k€/MW, almost 10 times less.

HES graphic showing auctions’ results for different delivery years

Entering into force in January 2017, the current mechanism is set to expire in 2026, which means that important high-level discussions are underway for its renewal and improvement. The first question on the table is whether France will need a capacity mechanism after 2026. Producers benefiting from the mechanism would like the mechanism to keep on in any case. Suppliers, while theoretically exerting a contrary force, desiring to keep electricity prices low, in fact tend to pass through the capacity price to consumers. Therefore, there is a formidable force in favour of renewing the mechanism independently of whether it will be necessary.

The other major question is whether the EU will allow France to adopt a new capacity mechanism. Although in its green transition the French electricity system will keep on benefiting from a huge modulable power source, nuclear, while other countries leverage much more on weather-random wind and solar. It is nonetheless true that renewable sources will play a key role in France as well. In this new European context, with high intermittent renewable power generation, the EU considers national capacity mechanisms a useful device to ensure system security, unlike before when they were considered a barrier to a free market. For sure, any capacity payment decided by any member state must be checked by the EU authorities to make sure that it is not disguised as state aid.

What will the future French capacity mechanism look like?

The new system aims to tackle several of the weaknesses of the current one. Joining UK and Italy, as shows from high-level discussions coordinated by the national grid operator RTE, the system is directing itself towards a centralised capacity mechanism, with RTE as the main counterparty. There will be fewer auctions than now and strict obligations to certify in advance. This will allow a significant simplification for all participants and increase the foreseeability of capacity available 4 years in advance. Moreover, the main auction being held 4 years in advance, this ensures that actors will have a clear price signal. Of course, the natural counter-effect, with a beneficial decrease in financial risk, would be that market participants will have less ability to adjust their positions and to maximise economic benefits.

The current developments increase the importance of closely monitoring the regulatory process, as one of the main sources of revenue for capacity and flexibility providers for the coming decades is under formulation. For some energy actors, the capacity mechanism represents a sizeable fraction of their yearly revenues, especially when they do not operate all year round but mainly during high price periods.

From the customer’s side, the cost of the new capacity mechanism will be like other network charges. No more management or hedges on prices will be possible under the new mechanism. However, strategic decisions can be taken because peak shedding and shifting will still be valuable as cost withdrawers.

As the new mechanism is still under discussion, we recommend producers and suppliers to participate as much as possible while some debate is open, to maximise profits and contribute to regulatory developments. You can count on HES both thanks to its consolidated experience with the French capacity mechanism and its continuous monitoring of European markets and regulation.

Enea Albertoli