Just a few days into winter, EDF has only 39GW available out of a total of 61.4GW of its nuclear fleet. These figures are the consequence of a series of events that have taken place since the outbreak of COVID-19, hitting the French nuclear fleet and reducing its production, which in the past had steadily represented almost 70% of the French electricity generation mix.

In this sense, last October the company had to cut its generation forecasts for 2022 down to 280-300TWh, a 30-year historic low. However, these new forecasts are not exactly a surprise, as EDF has been publishing for months now its availability forecasts for the French fleet with a clear downward trend. This, in despite of the company’s historically optimistic view of availability figures.

Therefore, the outlook for the upcoming months is complex. The decrease in nuclear availability comes at the worst time – with winter just around the corner and gas reserves which, though largely full in various European countries, have been subject to an uncertain future since the start of the Ukrainian conflict. To understand how we got ourselves into this situation, it is worth going through the main events of recent years.

COVID and lockdowns: the starting point

In March 2020, after the World Health Organization declared COVID as a pandemic, France issued mandatory confinement rules for its citizens from the 17th of that month. Even though this did not affect the normal operation of nuclear power plants, it did however affect their maintenance and overhaul schedule. Due to this lockdown and derived restrictions situation, maintenance works at several plants were either rescheduled or postponed (even the initial start-up of one plant had to be postponed). After the March lockdown, the government issued a second one in November, which resulted in further setbacks and delays that would prove problematic in the long run. Note that all these delays were taking place precisely in the midst of the “Grand Carénage” programme – first implemented in 2014 and due to end in 2025. This plan aims to improve the safety and to extend the lifespan of all French nuclear reactors beyond 40 years.

As lockdown measures were relaxed, nuclear plants were faced with altered schedules and delays the following months. The impact of COVID led to a reduction in electricity demand that allowed to get over the 2021/2022 winter without any major disturbances. Still, the nuclear fleet was already showing some signs of weakness.

Post-pandemic recovery and the arise of new challenges

At the beginning of 2021, with the ten-year maintenance programme already under way, the impact of the health crisis was mainly felt in the form of a delay in the maintenance schedule for winter 2021/2022. This put some pressure on the French nuclear fleet despite the good availability level of the first half of the year. In September of the same year, EDF announced further modifications to its maintenance schedules, which resulted in a decrease in availability for the last part of the year.

Nevertheless, what would turn out to be one of EDF’s biggest problems in previous months was yet to be revealed. In mid-December, EDF reported to the ASN (Autorité de sûreté nucléaire, the independent entity in charge of nuclear safety in France) that certain cracks found in the welds of the cooling circuit of Civaux and Chooz reactors (the most modern ones of the fleet) corresponded to a phenomenon called stress corrosion cracking (or SCC). As investigations developed, it was decided that a detailed inspection of all reactors in the nuclear fleet was necessary to determine which reactors were actually affected by this phenomenon. These inspections, essential to ensure the safety of production, only added additional pressure to the already dwindling nuclear fleet availability.

In February 2022, EDF lowered its production forecasts from 300-330 TWh to 295-315 TWh, as the nuclear fleet was being severely conditioned by maintenance and overhauls works. More specifically, the overhauls due to the SCC issue result in very hard to predict downtimes as the reactor must first be rendered inoperative for the necessary checking to be carried out (which already implies some downtime) and, should any indications of SCC be found, the reactor must be taken out of service until those repairs deemed as necessary are completed.

In August, while a large heatwave was hitting Europe, some reactors had to shut down production due to high water temperatures in nearby rivers used for cooling purposes, combined with an unusual increase in electricity demand due to extreme temperatures. Nuclear unavailability led electricity price figures to increase above the 1,000 €/MWh mark in August.

Afterwards, in the month of October, and during a widespread movement of wages discontent in France, operators from 20 plants (more than a third of the total) went on strike. At 17 of these plants, maintenance schedules were altered, ranging from 3 days in some cases to three weeks for the most affected.

To make matters even worse, last November the ASN required EDF to carry out additional repairs to the reactors of a specific plant affected by SCC. The authority based this requirement on the fact that there were some uncertainties regarding the checks carried out by EDF on the welds of the reactor pipes, and therefore these had to be repaired before the reactor could be restarted. Although there is no information indicating whether this request has been extended to other reactors or not, this requirement raises further questions as to the evolution of the problem originated by the SCC.

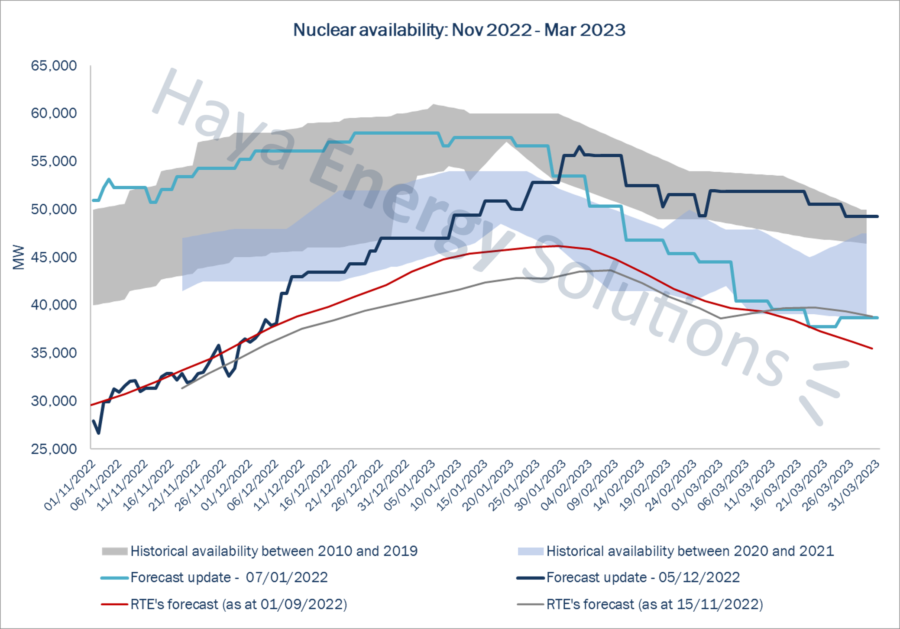

Figure 1: comparison of unavailability forecasts made by EDF at the beginning of January 2022 and at the beginning of December 2022, contrasted with the view of the French transmission grid operator, RTE. Created with HES NucMonitor©.

Figure 1: comparison of unavailability forecasts made by EDF at the beginning of January 2022 and at the beginning of December 2022, contrasted with the view of the French transmission grid operator, RTE. Created with HES NucMonitor©.

Altogether, these situations led to the current context, with a recovering production fleet but with a great challenge ahead. Currently, in the middle of December, only 63% of the fleet is operational (39 GW, i.e., 40 reactors out of 56). The question of EDF’s ability to get through the winter with its fleet in proper working order remains open. Futures markets have been extremely sensitive to this situation and, consequently, values for Q1 2023 have reached levels of 1,900 €/MWh. All this, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that EDF has continuously shown, via its transparency portal, a very optimistic view of the future return to operation of a large part of its fleet. And it is not only about EDF. In fact, at the end of October, French president Emmanuel Macron assured that 45 of the 56 reactors would be operational by January 2023. RTE, the transmission grid operator, has consistently maintained a more conservative view of the nuclear availability situation and did not foresee more than 46GW of availability at the very best for this winter. This view seems to be prevailing, as can be observed in Figure 1.

Moreover, all these situations have an additional consequence: France, historically a net exporter of electricity for the European continent (accounting for almost 15% of the region’s total generation), will find it very difficult to supply neighbouring countries this winter. In fact, in summer 2022, the French electricity system became a net importer for the first time in 42 years, having to rely on imports from Germany and Belgium, while it would usually be France that would be exporting electricity. This suggests that, while the French generation fleet could recover to meet domestic demand during the winter, it may not be able to do the same to regain its status as an electricity net exporter.

In conclusion, as maintenance works on the French fleet progress, a large number of plants are expected to return to the grid in the coming weeks, so the focus is on the evolution of these reconnections, since any delay could cause even more complications. On the other hand, it is worth noting that the French nuclear generation fleet has an average age of 35 years and, with the passing of time, problems such as the one currently being experienced due to the SCC issue could be repeated in the future, creating new stress cycles on a production fleet with many decades of operation on its back.

The question of how the French electricity system will get through this winter is still up in the air. However, if the scheduled return to the grid of some reactors in the coming weeks does actually take place and EDF manages to get the problems caused by the SCC issue under control, France could confront this winter without any major problems. HES has developed the NucMonitor© tool, which provides useful bi-weekly updates on the availability of the French nuclear capacity, and which can be of great interest to anticipate market reactions. The coming months will be crucial for the evolution of the French nuclear fleet. We will keep you updated!

Danilo Pich Ponti