As per Royal Decree-Law 3/2023 of 28 March this year, approval was given for the extension of the Iberian singularity, a mechanism that allows Spain and Portugal to “intervene” in the electricity market to reduce the impact of the energy crisis on end consumers. At the time, this piece of news caused a stir, being the talk of the media which, without fully understanding the purpose of this mechanism, heralded the results of the daily electricity market by announcing record highs.

The news of the extension, however, has gone almost unnoticed. The focus is now on other issues. Interest in the electricity market has been lost, perhaps because prices are no longer as high as they once were. But do we really know what impact this mechanism has had on the end consumer, and has this measure fulfilled its objective?

In this article we will try to answer these questions.

On 15 June 2022, the ‘Iberian exception’ came into force, with an initial duration of 12 months. The idea was simple: to limit the price of thermal generation offers in order to reduce the marginal market price. In theory, the consumer would pay a lower price for the electricity consumed and for the compensation to gas producers, the total cost being lower than what they would have paid without this mechanism due to a question of volume: the cost of gas is only paid for the electricity produced with gas and not for all the electricity generated as would be the case without this mechanism. (For more details, our previous articles on this subject are available: THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ – Iberian Singularity & Analysis of the Iberian Singularity (last 3 months).

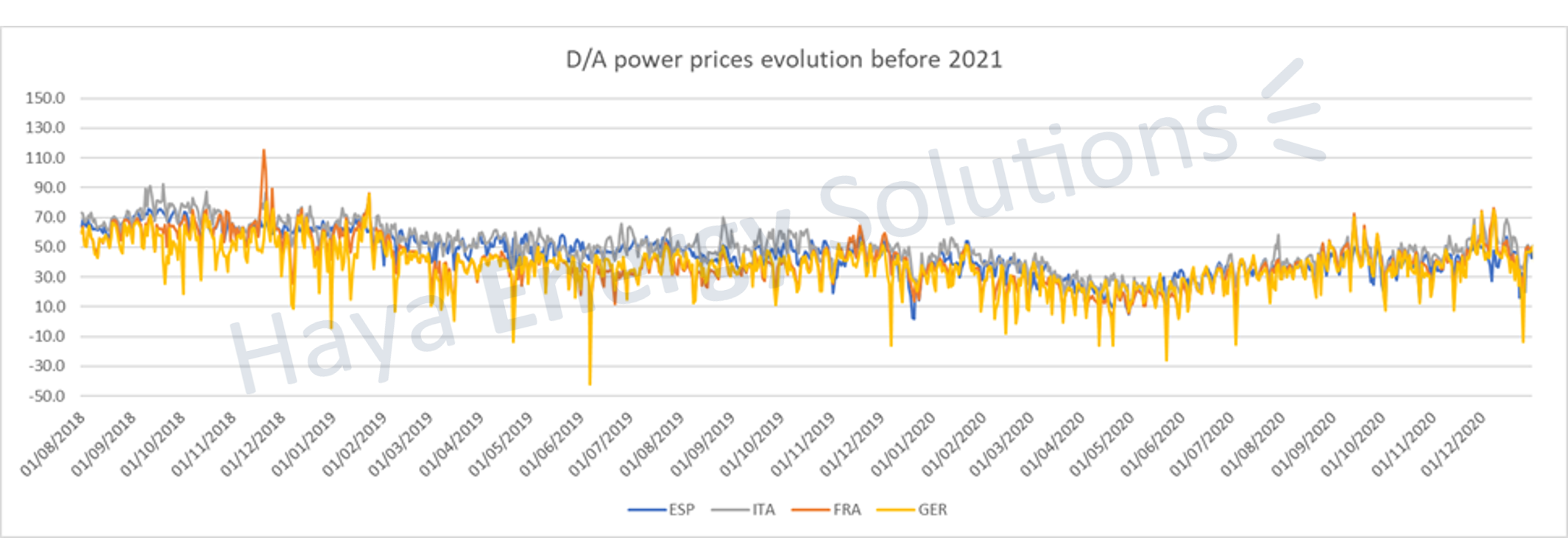

Looking back, in recent years the price of electricity in Spain has followed the same trend as in the rest of Europe, with the average price being higher than in other countries such as France and Germany, but lower than in countries such as Italy.

Between 2018 and 2020, the average daily electricity price in Spain was just under 49 €/MWh, slightly higher than in France (44.5 €/MWh) and Germany (40.5 €/MWh), and lower than in Italy (54 €/MWh).

In 2021, post-COVID economic recovery significantly increased energy demand. However, COVID itself meant that energy infrastructures were not in top shape (many maintenance operations and investments were postponed during the pandemic) which, coupled with adverse weather conditions in many parts of Europe, meant that supply had difficulty meeting demand and therefore electricity prices started to rise.

In the midst of all this, Russia began to cut gas supplies to Europe as a measure of pressure in response to its military manoeuvres on its border with Ukraine, increasing the price of gas and, thus, the price of electricity. Unfortunately, Russia decided to invade Ukraine in February 2022, which worsened the situation: Europe applied a series of sanctions while Russia increasingly restricted gas exports to the EU.

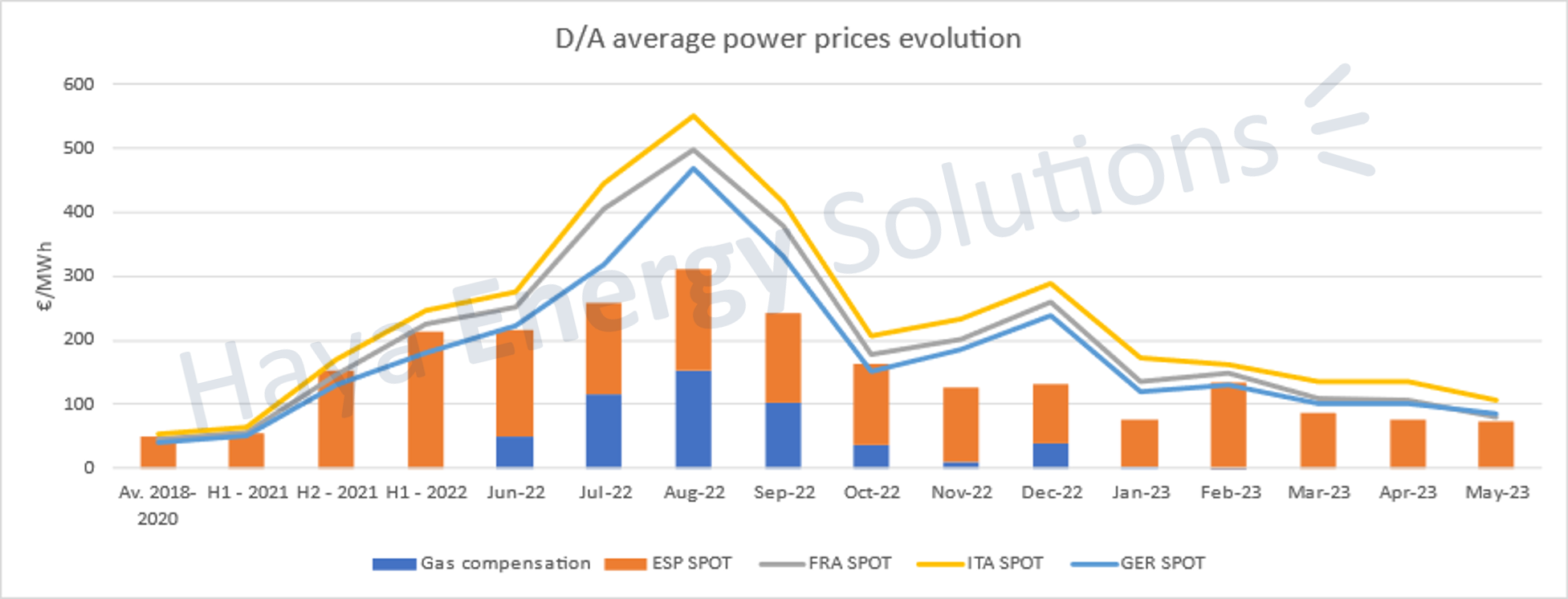

In Spain, prices rose from an average of less than €49/MWh in 2018-2020 to an average of €153/MWh in the second half of 2021, and to an average of €214/MWh in the first quarter of 2022. This soaring increase in prices was experienced across Europe:

As can be seen in the above table, France and Germany show a higher price increase than Spain or Italy. This is because western Europe had an added problem at the time, the poor availability of French nuclear assets, key to electricity supply in the area. For more details, see our Newsletter: Nuclear energy in France: a challenge ahead.

And it was at that moment, with average daily prices setting records day after day, that the ‘Iberian exception’ came into play after difficult and lengthy discussions with the European Commission. The graph below clearly shows how, before the entry into force of the Iberian mechanism, electricity prices in Spain were around the levels of other European prices whereas, since its entry into force, the final price passed on to consumers[1] has been lower than the European average. Specifically, 57% lower in the second half of 2022 and 28% lower so far in 2023.

This study could be refined by calculating what the average daily electricity price would have been without the impact of the gas price cap and comparing it with the price passed on to consumers. However, the above results clearly show the positive outcome of this mechanism, irrespectively of any quantitative adjustments that a more in-depth analysis might yield.

Some operational aspects of the ‘Iberian exception’ have been controversial. For example, the way in which the price adjustment of the mechanism is passed on to final consumers, out of step with the cost of energy. This leads to cash mismatches at final consumers level, precisely one of the problems that was intended to be avoided.

Another aspect to be considered are the market signals: if electricity prices remain low in times of an energy crisis, there is no incentive to save on electricity consumption. In fact, if one compares electricity consumption figures for 2022 with those for 2020, there is hardly any reduction in demand. However, the signals are still present, albeit tempered, in the bills of consumers who have seen their costs rise significantly.

There has also been some speculation about how the Iberian exception deals with interconnections with France, and whether Spain is subsidising French electricity. Firstly, it should be noted that the Iberian Peninsula’s interconnections with France are minimal, barely 2.8% of Spain’s installed power capacity. It is precisely this minimal level of interconnection that has allowed this exceptional mechanism to be approved – the impact for the rest of Europe is considered negligible. Secondly, the congestion rent ensures that France pays 50% of the cost differential of exported electricity (price difference between Spain and France) to Spain. Taking this into account, consumers in Spain are effectively paying for a gas cap compensation from which France partially benefits.

All in all, the ‘Iberian exception’ seems to fulfil its objective of protecting consumers from rising electricity prices. Moreover, it does so without substantially affecting the free market (unlike the tariff freeze that led to the tariff deficit at the beginning of the century). There are certainly some aspects that could be improved, but it has been proven that decoupling electricity markets from the price of gas is possible and can be useful in times of crisis such as the one we are going through. The proposal on the electricity market reform led by Spain and supported by other countries such as Portugal and France was based on this concept, and proposed a structural decoupling of technologies such as combined cycle or storage (see Newsletter: Electricity market reform: Spain’s proposal). However, the status quo usually prevails in the face of such far-reaching changes, and Brussels’ final proposal does not include any such mechanism.

Manuel Domínguez León

[1] Daily electricity market price plus compensation to gas producers for the gas cap.